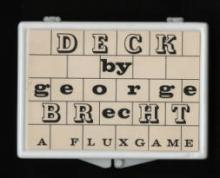

Game

AMONG THE THINGS that Fluxus possesses, or so said Ben Vautier, is “wit,” “no money,” and a “sense of game.” Draw a map to get lost. Play baseball with a piece of fruit. Notably, many Fluxus events, scores, and instruction pieces were first conceived as or alongside of games—George Brecht’s Fluxus Games and Puzzles or George Maciunas’s Flux Snow Game, for instance. Games transform sets of instructions into phenomenological experience. They are vehicles for spontaneity, novelty, and creative play. Games encourage sensual engagement, both with the art object and with others who play. In this regard, Fluxus games break the art museum’s cardinal rules of no touching and no talking, since a sizeable body of Fluxus works requires tactile contact and social interaction. But unlike many traditional games, which depend upon a sense of pleasure derived from goal-driven competition, Fluxus games emphasize joyful absurdity, curiosity, and collective life.

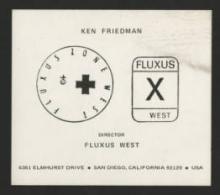

Mail

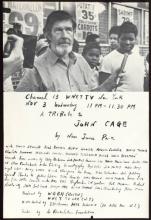

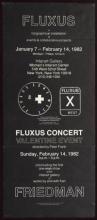

LETTERS, POSTAGE, POSTCARDS, handstamps, and postmarks—correspondence between artists, the instruments used to mark their communiqués, even the postal system itself—were seen as essential elements of artistic work and community. Here, we encounter Fluxus’s signature emphasis on process over product, the conflation of art and life, and a preference for ephemeral and affordable materials. Yet we also encounter a preoccupation with networks and their subversive applications. George Brecht and Robert Filliou coined the term “Eternal Network” to describe “an international center of permanent creation” through the post. Fluxus artists played a central role amid a wider network of minimalist, conceptual, pop, and performance artists who adopted a practice sometimes called “correspondence art” or “mail art.” The significance of movement is expressed in other ways. In the mid-1960s, for instance, Ken Friedman had at the behest of George Maciunas become Director of Fluxus West, covering activities in the western United States. Friedman set up centers in San Diego and San Francisco. He later bought a Volkswagen bus and dubbed it the “Fluxmobile,” which Friedman described as a “traveling” exhibition, studio, and publishing house. The Fluxus West postmark is found throughout this collection, and may be traced to Friedman’s prodigious work.

Event

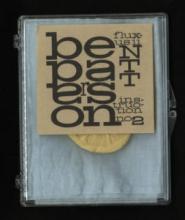

DICK HIGGINS proclaimed that Fluxus “did concerts of everyday living.” “Coffee cups,” he remarked “can be more beautiful than fancy sculptures …. The sloshing of my foot in my wet boot sounds more beautiful than fancy organ music.” Hannah Higgins deftly observed two crucial formats among Fluxus artists: the event and the fluxkit multiple. The first is an experiment of poetic, musical, theatrical, and cinematic variation in which everyday activities are framed as performance. Events are simple, direct actions meant to dissolve the distinction between art and everyday life. George Brecht’s Keyhole Event for example: “through either side one event.” In Mieko Shiomi’s fluxfilm titled Disappearing Music for Face, a person’s lips slowly close over a period of eleven minutes. The fluxkit multiple, on the other hand, refers to cases and boxes of various sizes that typically contain small objects, cards, and various text-based works. And because event scores were frequently housed in fluxkits, making them ephemeral and portable, the two formats are integral to one another. The viewer may choose to read these works privately or perform them in social environments.

Object

AFTER PRINTED MATTER and performed events had proven furtive testing grounds for Fluxus activities, by the mid-1960s sculptural objects began to appear with greater frequency. The preferred materials are telling: wood, glass, plastic, and rubber. They are quotidian materials we associate strongly with everyday use, and, dutifully, Fluxus objects were meant to be touched. All were affordable, plentiful, and easily replicated. Ay-O’s Finger Box is precisely what it sounds like: a 7.5 x 7.5 x 7.5-inch square box with slits on two of its sides, inside of which an unspecified material blankets one’s fingers. Many Fluxus objects bear the mark of the group’s most significant precursor: Marcel Duchamp, creator of the “readymade.” The found object forms one of the core practices of Fluxus. If the found object dissolves the boundary between art and life, making the materials of everyday experience the stuff of artistic expression, then it also questions notions of ownership and artistic pedigree. Notably, a number of donated objects in the Fluxus Digital Collection lack full documentation; in some cases, no author, date, or year is specified. And since personal items sometimes accompany donated works, it is not always clear which objects are indeed artworks. The difficult situation this presents for archivists would not have been lost on Fluxus artists!

Paper

A SIGNIFICANT NUMBER of Fluxus works consist of printed matter: manifestos, charts, signs, maps, posters, flyers, newsletters, newspapers, and small magazines. Like many avant-garde groups of the twentieth century, Fluxus took advantage of key innovations in independent publishing. In an age of mass production, the tabletop letterpress and the mimeograph machine offered writers and artists greater control over the work they produced, and at more affordable costs. George Maciunas’s News-Policy-Letters allowed a community of artists spread across North America, Europe, and Japan to keep apprised of one another’s activities. Publications like Decoll/age, Fluxus Preview Review, ccV Tre, and imprints like Something Else Press promoted artists working outside and between the conventional borders of genre and format—or what Dick Higgins called “intermedia.” Furthermore, the effects of letterpress printing evident in many fluxkit and mail-art designs also extend to other modes not traditionally associated with art. Maciunas’s chart “Fluxus (Its Historical Development and Relationship to Avant-Garde Movements,” Nam Jun Paik’s map “Fluxus Island in Décollage Ocean,” and Wolf Vostell’s diagram “Fluxus Wiesbaden 1962” are exemplary works that appropriate from genres germane to fields and techniques of geography, history, and the social sciences.